fragments

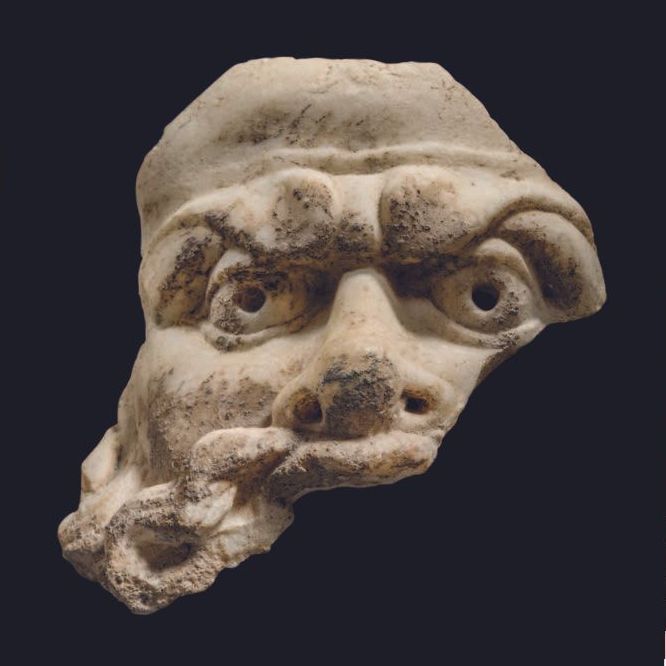

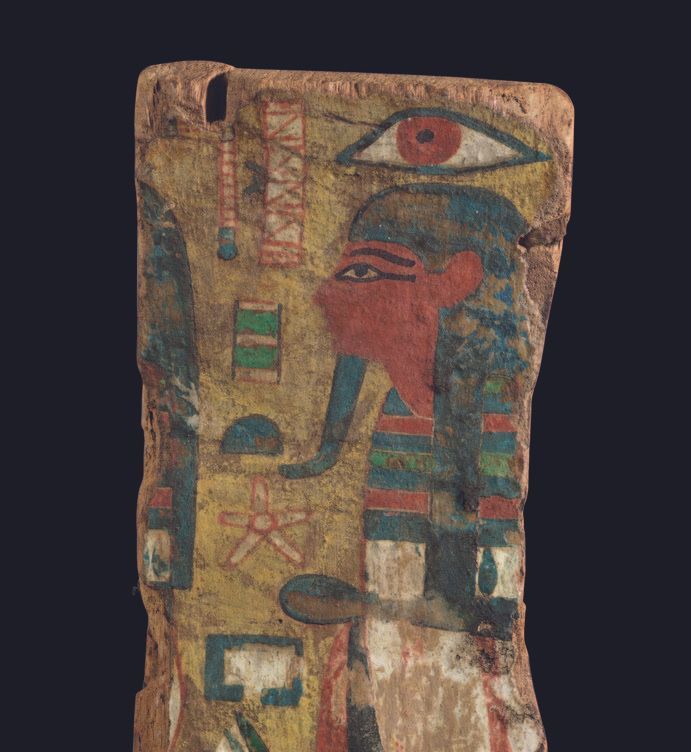

RUPERT BATHURST’S WORK summons ideas of damage and fragmentation, but also points towards transformative reordering. In this respect a shared exhibition entitled Fragments,¹ of Bathurst’s work alongside the rare and beautifully fragmentary antiquities of Rupert Wace, is entirely appropriate and mutually complementary. Wace shows works, often damaged in the course of their long histories, that are of classical, near eastern, ancient Egyptian, and prehistoric European origin. There are theoretically constructed and serendipitous correspondences between the two exhibitions, as brought together in one viewing space.² Their typologically diverse objects and depictions may include symmetries and asymmetries, patterns, and sometimes the profound and mystic. Overall, the premise of the exhibition has a value and relevance beyond just the pleasure and interest of old and new art in proximity with each other.

Bathurst and Wace’s exhibition has two accompanying publications: one for Bathurst’s contemporary work, and one for Wace’s ancient rarities. This publication addresses Bathurst’s work... Ideally there would be a third publication, with a text by a poetic thinker, which addresses the greater sum of the two exhibition parts...

If order is a defence against fragmentation and collapse, then fragmentation and collapse may not only be a consequence of, but be a defence against, order. How order and disorder are defined – whether they are perceived as damaging or not – will vary by culture and historical circumstance. Perception will also depend on individual sensibility. At a personal level, physical and mental suffering may drive an immense psychological wish towards disintegration and disarray, and even to a wish for actual extinction... or, if the gods are favourable, to transformation and new forms of healing and being.

Bathurst lives on land on which are the ruins of a Roman temple – a cult centre of the Romano-British god, Nodens. The Temple of Nodens was established in the late third or early fourth century CE and was host to a number of mystical practices, with the Romans having appropriated many practices and spiritual values of Celtic origin, especially as they related to healing and curative work. It is believed that the Temple may have had a designated area for the sick to sleep and experience visions of divine presence in their dreams. Celts had animistic and shamanistic cultures, and placed a high value on dreaming, which was believed to contain messages from the otherworld... a ruined mosaic in the Temple makes a written reference to dream interpretation...

Depending on which etymologically confusing sources are consulted – Christian, pagan-witchcraft, or other – the nursery phrase ‘Land of Nod’ refers either to the god Nodens or to a geographical area of lost, excluded wandering, called Nod, described in the Bible (Genesis 4:16). Both summon mythical ideas, sometimes based on obscure derivations, or magical puns, that describe an ‘other place’, and both are claimed to be the origin of the expression ‘nodding off’, referring to a place of dreams. Opiate addicts use the expression ‘nodding off’ to describe the sleepy, dreamlike changes of awareness caused by narcosis...

Bathurst had a rock-and-roll youth, in which there was much Class A partying, and consequential destruction. Many years later, Bathurst has repaired the rock-and-roll errors, has a family, makes art, has co-facilitated notable artists’ projects, helps grow food for the nation, supports organisations that provide healing and curative work to addictions sufferers, manages sustainable forestry, and aspires to good ethical reflection, including the socio-economic.³

Bathurst’s art makes reference to damage and healing which could be described as depicting an imaginative world of super-vivid, almost shamanic energy; that is, energies of destruction and creativity, invoking the presence and absence of, and the journeying between, different psychic realms. It would be enjoyable to speculate that these healing activities have arisen from Bathurst having visions of divine presence in his dreams... but that would be an art-writerly speculation too far.

Many votive offerings were made at the Temple of Nodens, and some of these, or their fragments, have been found.

The offerings were made to a number of divinities, especially animal ones; animals being accorded a status as having special healing power. A mosaic floor, with a reference to dream interpretation, depicts a sea deity and aquatic life, and this work of art (and its conservation repairs) can be thought of as being visually analogous with aspects of Bathurst’s work, if not an actual influence. Dogs were an animal particularly associated with healing and in the fourth century CE a bronze cast of a dog was placed, for therapeutic reasons – a votive offering – within the Temple site. As an archaeological treasure it is known as the Lydney Dog.⁴ Yet another animal representation that Bathurst grew up with has a human face and it may, possibly, have been a biomorphic representation of the god Nodens taking the form of an animal. The Lydney Dog, and its historical relationship with negotiated healing, and Bathurst’s art and its relationship with healing, become – when situated amongst Wace’s multitude of deities and spiritual intermediaries of many religions, faiths, and times and places – part of a totalising mystic continuity...

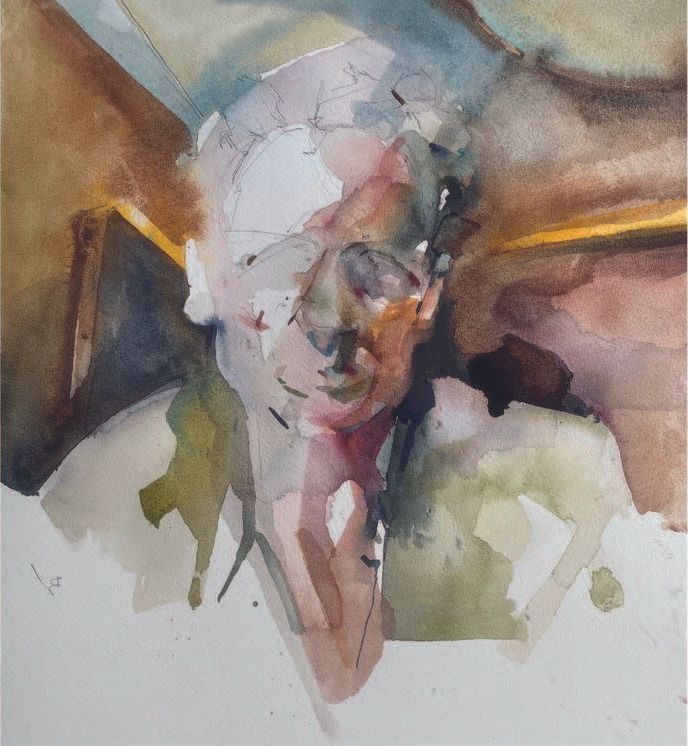

Bathurst has many stylistic interests, and a diversity of ideas and subjects. He makes portraiture that is divided between, or is on a continuum of, traditional representation or more interpretive portrayal. These portraits and portrayals sometimes involve fragmentation of appearance, sometimes impeccable wholeness, and sometimes fusions of both, of which Self Portrait and Rupert Wace (both 2023) are examples of the fused.

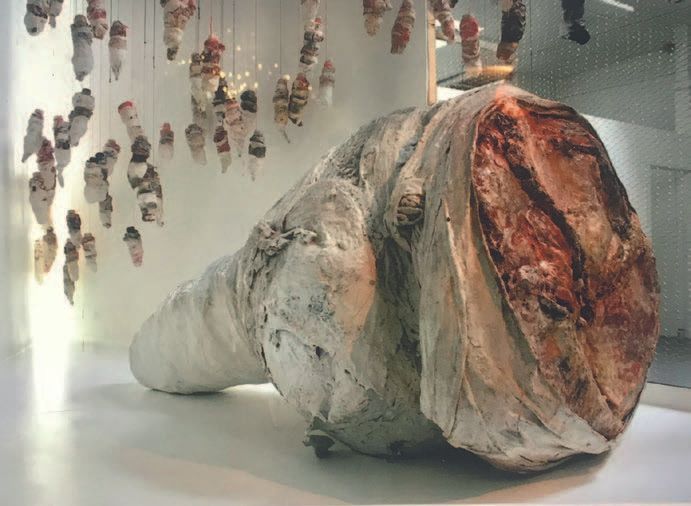

Bathurst makes physical sculptural objects which (although not in the Bathurst–Wace exhibition) are consistent with his themes, where they relate to ideas of damage. These works, Experiments (2014–15), have an emphasis on dystopian abjection – physically ill, fleshly abominations – and are an epitome of Bathurst’s interest in biomorphism.

Less abominably, there is a huge series of 120 individual faces observed at online Zoom meetings Zoom Connection (2020–23) where, under the life-diminishing grip of Covid, and its lockdowns, people gathered – connected together, digitally – for mutual support and wellbeing. Meditations (previously Neurodoodles) (2005–23) are watercolours, which continue, in part, Bathurst’s theme of abomination, but also the fevers of sexuality, bodily physicality, illness, emotional derangement, relationships (for better or worse) and, ultimately, transformative wellness. From 2018 the Meditations series expanded to give shamanic forms of attention to behavioural and addictions disorders and made visual certain aspects of behavioural disorders recovery therapies. A series sequence The Journeyman (2021– 23) creates a narrative progression – A Rake’s Progress in reverse – from despair to the redemptive.⁵ Large abstract works Falling Angels (1998–2021) seem to be elemental mood boards – the accretions and discharges of a psychic history, in which individual parts become a whole, in what seem to be inexorable moods, of emotional enormity...

In 2015 and 2016 a series of artist residencies took place on Bathurst’s land, known as the Blackrock and Matt’s Gallery Residency Programme. Curatorially originated by Robin Klassnik from Matt’s Gallery, Roy Voss, and Bathurst, the project enabled participating artists to enjoy accommodation, materials, workspace, and time, to make art that would otherwise most likely never come into existence. There were seven artists in the residency scheme, who made work in what was Bathurst’s rural home environment.⁶ Although Bathurst was a co-curatorial director, with Klassnik and Roy, and not one of the artists, it would be an interestingly reflective thought-exercise to imagine him as an artist beneficiary of a such a scheme – as having been accorded a lifetime’s accommodation in a countryside environment, and given the time, and sufficient resources, to be, and think, and make art...

NEAL BROWN, 2023

- Rupert Bathurst and Rupert Wace, Fragments, Shapero Rare Books, London. June–July 2023

- In 2017 Sophie Hicks curated an exhibition, Dizygotica. With unlikely subversion, Wace’s antiquities were paired with rare, vintage postcards from the collection of the art dealer Kasmin.

- Bathurst has instigated an inventory process to further recognise, and detail, the contribution of the Atlantic slave trade to the wealth creation of his ancestors.

- Another votive bronze dog was found in 2017.

- William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress was a narrative series of paintings, depicting addictive dissolution, made in the eighteenth century.

- The artists were Patrick Goddard, Sally O’Reilly, Alison Turnbull, Rebecca Birch, Bronwen Buckeridge, David Cheeseman, and Roy Voss, with special contributions by Susan Hiller and Willie Doherty. The Blackrock and Matt’s Gallery Residency Programme was generously supported by Arts Council England and the Jerwood Charitable Foundation.