Its Own Devices

Essay by Linda Taylor.

Residency with Henry B Bruce in The Pithay building, Bristol.

January 2017

Returning home on dark winter evenings I occasionally have an uncanny sense that the empty house, on noting the sound of my key in the door, abruptly halts some secret activity and musters itself to appear unchanged since my departure. A flick of the light switch arrests each room into a suspiciously exaggerated and breathless stillness – as when the music stops in a game of musical statues. It is an irrational and terribly anthropomorphic notion, for sure. But, as Italo Calvino is convinced in an undelivered lecture titled “Visibility” in Six Memos for the Next Millennium (1985), ‘our imagination cannot be anything but anthropomorphic.’ What might an empty space do in an interlude between people and purpose? Might windows tell stories to walls – not with spoken words – but with darkness and light and glimpses and rumour? Left to its own devices, might a darkened room invent cinema or at least the possibility of cinema? Well yes. It might.

Camera originates as Latin word for an architectural space: a chamber. Obscura translates as dark. A dark room is a camera obscura, the predecessor of photography and cinema, in which images from outside are projected onto inside surfaces by means of an aperture … a hole … a gap. Cameras obscura may occur autonomously, as appears to be the case in Prague Castle where an image of the neighbouring New Royal Palace is projected onto an attic wall via a hole in the roof. Some academics suggest that Palaeolithic cave paintings were made in response to the phenomenon – which would situate the camera obscura not only at the dawn of photography but at the dawn of art itself. If cinema originates in space left to its own devices, Virginia Woolf, in her 1926 essay “On Cinema” begins, in turn, to guess at ‘what the cinema might do if left to its own devices’ – when its practitioners give up imposing existing forms upon it and allow the nascent form itself to mine and exploit its own peculiar capacities.

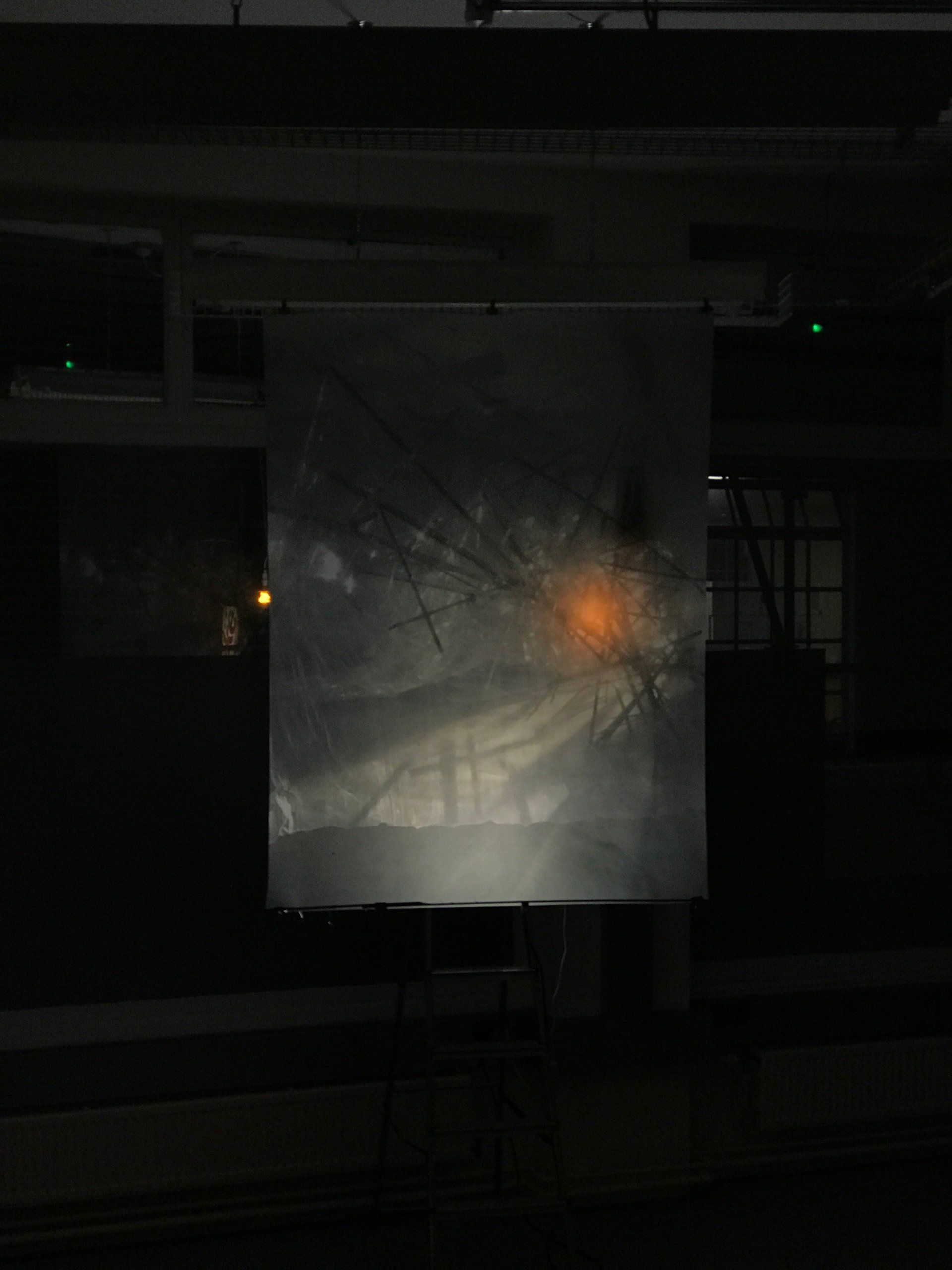

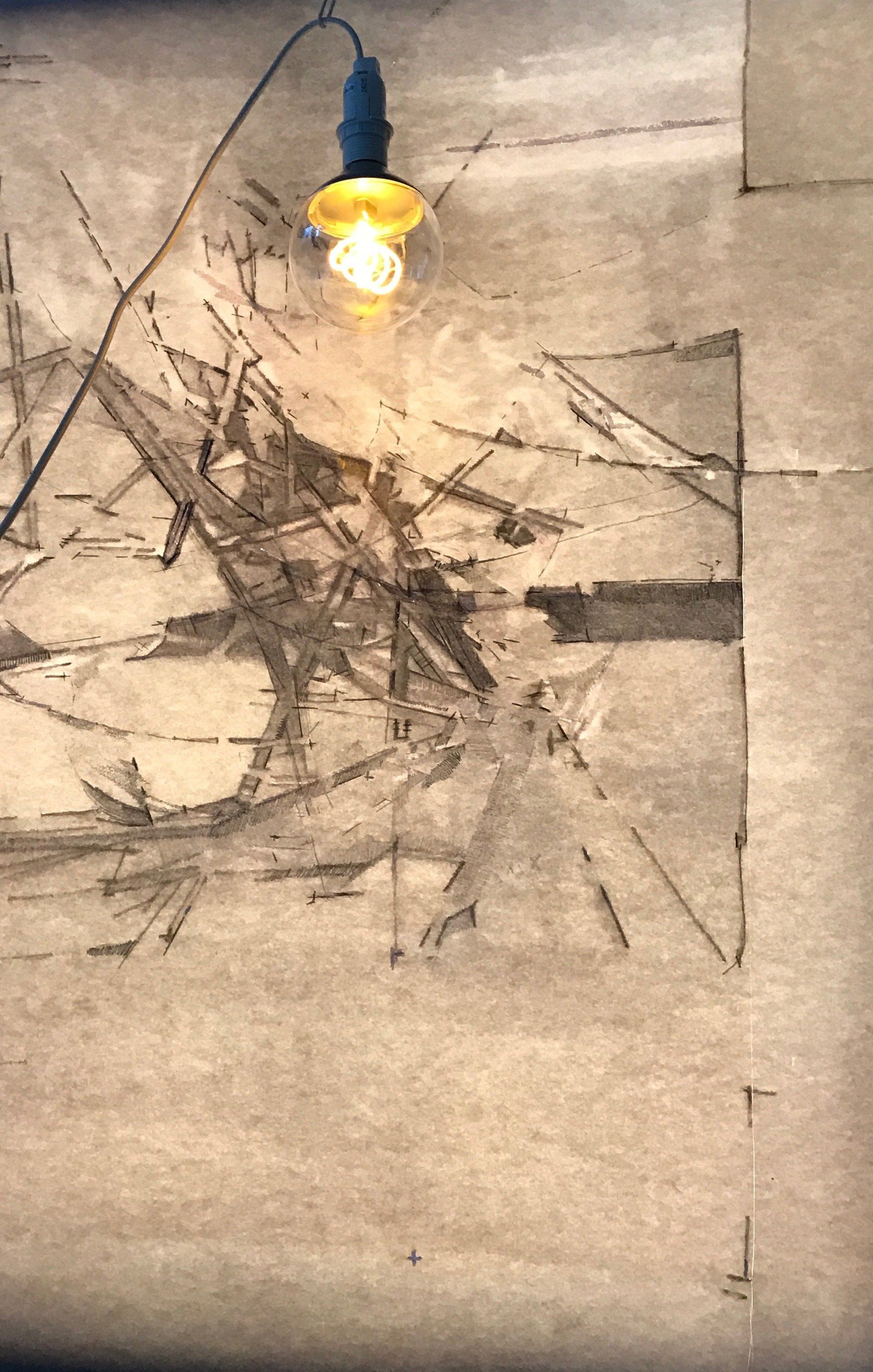

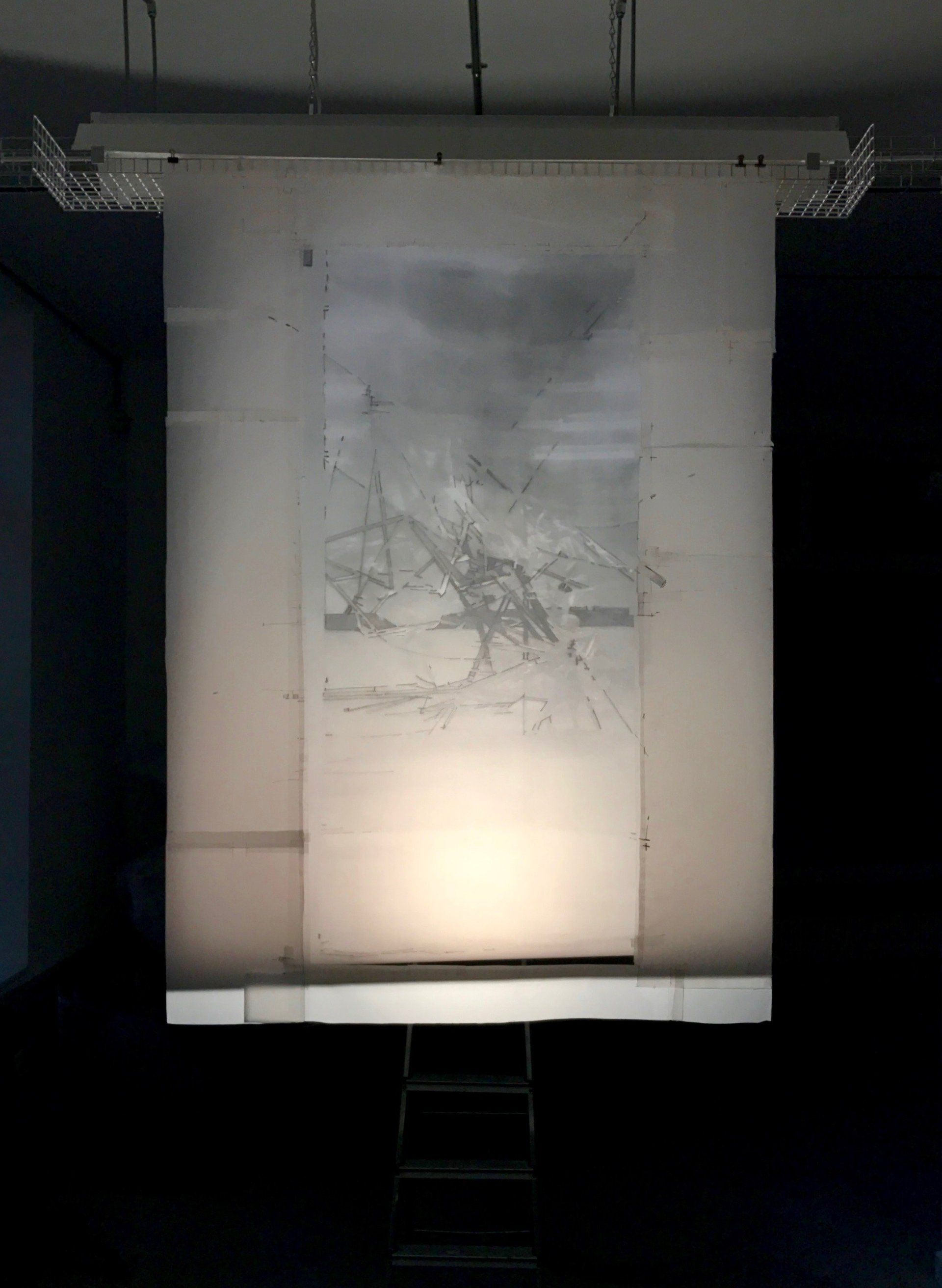

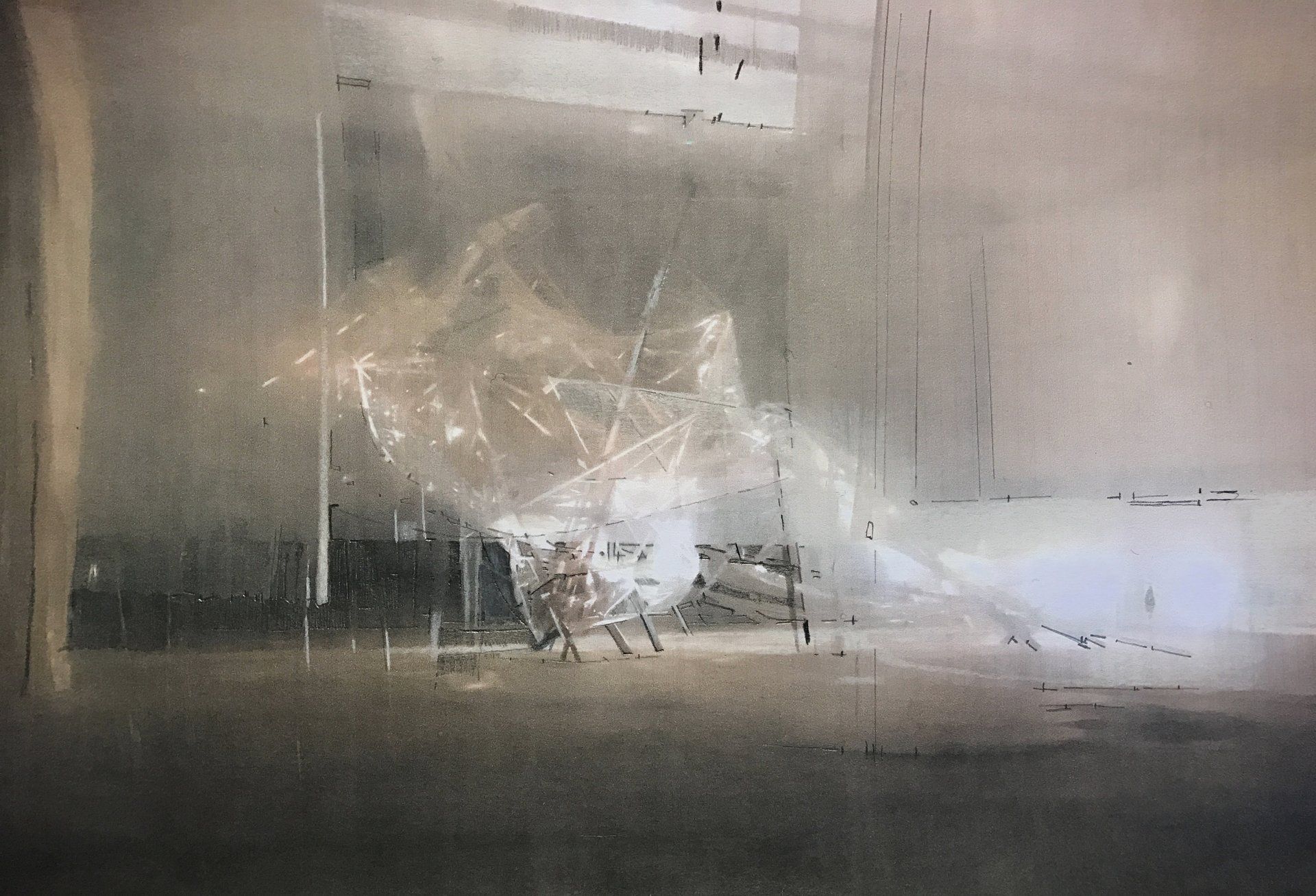

Such is the restraint and sensitivity of Rupert Bathurst and Henry Bruce’s installation (I should like to call it an interlude), in a vacant office space in the centre of Bristol, it is possible for the anthropomorphic imagination to suppose that the space itself has made its own fictions in the gap between people and purpose (I overhear a visitor wonder whether the artists have noticed an apparently incidental play of reflected water which strips the ceiling and penetrates the glass panels of the enclosed stairwell). Windows walls ceiling and floor regale one another with the imaginary and the might-be-real. Telling tales – without words – with darkness and with lights and with glimpses. The space projects its outsides onto its insides and throws its artificial shadows back at the city evening through glass darkly. A game of visual Chinese whispers: exchanged rumours pass up and down its staircase spine and morph as they navigate conduits of cables and pipes. Rumours from inside and rumours of outside. Rumours and glimpses of the city.

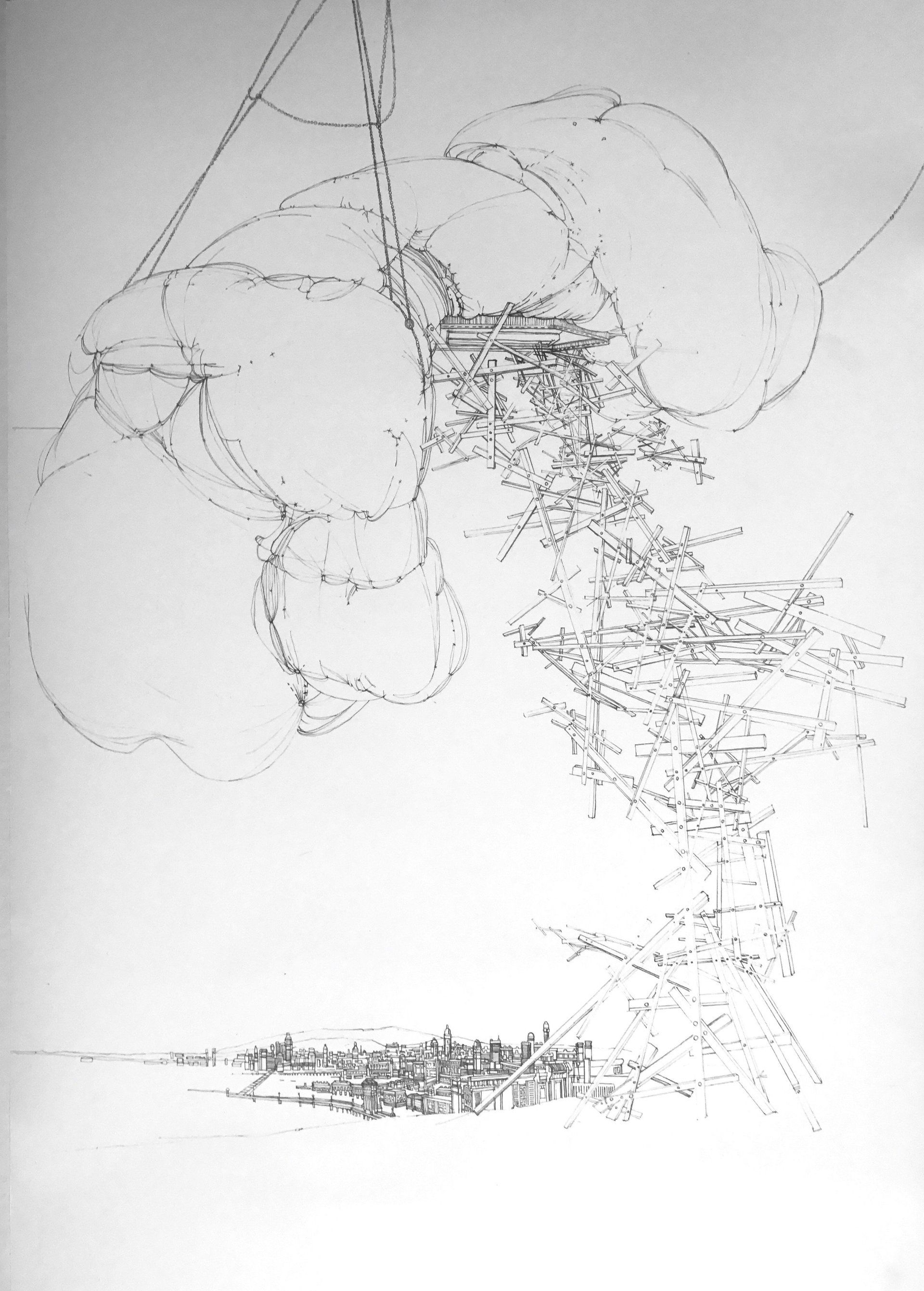

The city outside fidgets and strives, constantly remaking itself it is rarely, if ever, without some part of itself swaddled in scaffolding – a permanent impermanence. An armour of scaffolding envelops this building, protecting and screening its eight-storey pile of empty. The ubiquity of scaffolding renders it almost invisible to our accustomed eyes. But silhouetted and projected into the patient space – which repeats and reorganizes its form and scale – familiarity is dispelled and the nature of its reality shifts.

In this camera obscura … this lanterna magicka … in these silent movie frames, the banalities of the city evening beyond are not shuttered out but screened. To screen is to both conceal and to reveal. To screen: to hide or partially obscure; to block; to protect (from sun, wind and insects); to air on television; to show via projection. Woolf notes that things screened at the cinema become ‘real with a different reality from that which we perceive in daily life … As we gaze we seem to be removed from the pettiness of actual existence.’ Headlamps, reversing lights and brake lights, negotiating a multi-storey car park opposite the first-floor windows, dance across and skid off a suspended widescreen – like an elaborate Morse code relaying mysterious fictions.

Further screens fashioned from mundanely useful plastic sheeting might be – in this functionless arena – swathes of gossamer or the quivering walls of a translucent labyrinth which shrouds the stuck stick bones of some brooding bulk. The suggestive incompleteness of this partially obscured partially formed (or partially decayed) thing, offers myriad means of projection and conjecture to the anthropomorphic imagination. It might be (and this is my projection) an ancient waiting thing that dwells in spaces between people and purpose. In our presence it plays dead and awaits our absence … waits to be left to its own devices.